Some thoughts on the NYTimes article 'Magazines Begin to Sell the Fashion they Review' by Eric Wilson. Read More...

Read MorePart 4: Legitimizing the Luxury Brand (or, DIY Luxury)

To recap, there are three main points that a luxury brand must address in order to be considered "luxury" by consumers and other brands/competitors in the luxury community:

- The Material: this often translates to quality production and components, all the tangible extras, and typically a premium price

- The Immaterial: this is the symbolic factor; the status conveyed in brand association, group-affiliation, lifestyle buy-in

- Distance: this creates the sense of rarity, limited availability, difficulty in finding or obtaining... all things that lead to building a coveted item or name

The Gucci store in Ginza, Japan features a "gallery" on the top floor where patterns, cutting machines, bag components, images of Italian craftsmen and so on are all displayed. This demonstrates the craft in terms of a high art - the material. But look a little closer, and you'll see that this display achieves all three of the above points, communicating to Asian consumers the luxury brand association of the European powerhouse - the immaterial, and the sense of handcrafted, one of a kind products - distance.

So, what happens if you're not a European luxury powerhouse? Today's scene is ripe with emerging new brands trying to position in a luxury market dominated by the Louis Vuittons of the world. While it may seem that luxury status is limited to the brands who've been around the block a time or two, that is not the case. Today, consumers are demanding a more personalized, meaningful luxury, whether that comes in the form of handcrafted fashions from a local designer, wine from an unknown vineyard with a beautiful story behind it, leather goods from a young leathersmith who studied in Florence. Today, it's about going smaller, more niche, more personal.

Luxury Gets Little

In fact, my sister got married in June and instead of going through racks of the name brands, she had an original dress made from a designer she found on Etsy. Not only is the dress one-of-a-kind, but it's made from reworked materials (we're all into that sustainable, ethical, recycle-ish stuff!). Although this particular designer charges only a modest fee for her designs, my sister got a completely unique handmade dress made from valuable, limited vintage fabrics, and she gets an incredible story to tell.

So, can a $500 wedding dress from an unknown designer on Etsy be considered 'Luxury'? It is to my sister and to quite a substantial following of like-minded brides. The dress is well made, rare, and there is a symbolic value increasingly associated with this sort of homegrown design, very cool in some circles- especially the booming DIY niche. However, the designer is not verified with a heritage or a known reputation (although the social media avenue is working for her!). Once again, luxury is subjective.

So, if you're not among the PPR or LVMH brand superstars (which, as Marc Jacobs' President Robert Duffy mentioned in early 2010, will become increasingly impossible for young designers to achieve), how do you convey luxury status? Let's say you've just graduated from Parsons or Central Saint Martin's, and Naomi Campbell is not walking in your graduate show. In these days of the emerging amateur economy, the self-made man is making a comeback. The model for success may have changed, but you can still take some inspiration from the past generations of powerhouses and build your own star status.

Below are the symbolic qualifiers which legitimize luxury brands in the eyes of the market, along with some tips on how to fake it 'til you make it.

Proving Luxury, or "Authentication"

Heritage

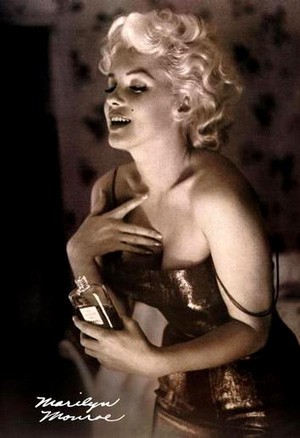

Chanel displays massive images of Coco Chanel in the headquarters and in boutiques, along with Warhol's No. 5 image, or a photo of Marilyn Monroe cradling the fragrance- all illustrating the iconic history of the brand and the pop culture status of a key product.

Louis Vuitton displays old trunks in their shops to demonstrate their roots in fine handmade luggage.

Gucci's website is populated with product, factory and storefront images from the last 90 years to reinforce the brand association with a strong Italian tradition in craft and luxury retail.

The Indicator: Luxury needs heritage. A "slowness" to a brand shows staying power and a timeless relevance. This relevance is often psychologically motivating for the consumer because - especially in the post-recession economy - shoppers want to know that they are dropping their hard-earned cash on brands that aren't going to be done tomorrow.

Hermes is good at this, drawing frequent references to the brand heritage in equestrian products. Chanel is good at this as well (in addition to references to icons of the past): the No. 5 bottle design has evolved slowly over the years so as to demonstrate a barely-noticeable change while keeping the bottle modern in appearance.

The Contender: Even if a brand doesn't have a heritage of fine Italian production that goes back several generations, a sense of history or continuity can be created through association or influence. Every designer takes inspiration from something that came before, whether it is another designer, a creative movement, a personified icon, a production technique, a place or something in nature. In order to build a strong brand identity that resonates in the luxury community, a brand needs to tap into this source of foundational inspiration and communicate it in a way that says, "This is where we originated." Be specific. Be creative. Communicate the story from many angles to make it rich and believable.

Service

This one is a little tougher to explain. The main point of service in luxury is to create a balance between accessibility and distance for the consumer. The role of service is to hold the product away from the customer while beckoning them towards it. It's like saying, "Come on, over here... that's it, come on- now STOP!" After all, part of the idea of luxury is in obtaining the "unobtainable." (As an aside, I believe this is also the reason why lapdances are so popular among half the population.)

Service (personnel, web, etc) represents the voice of the brand - the glimpse of the brand lifestyle that can be accessed by the consumer - and communicates it directly. However, unlike mass market brands, luxury brand service must be extremely sophisticated in how the brand values are communicated. It is not enough to say, "Welcome to ___. Let me know if I can bring some extra sizes to your fitting room." Rather, luxury service personnel take measure of the potential client. They get a feeling for what each client is looking for, make pointed suggestions, and discourage those occasional unfortunate purchases (bad for the brand image), and -most importantly- they give a portrayal of the brand lifestyle.

Ralph Lauren service is American aristocratic in both look and attitude. Prada service in understated Italian chic. Abercrombie and Fitch (right) borrows from this luxury concept, outfitting their stores (especially stores outside of the US, where the brand image is elevated) with chiseled sales assistants and doormen, providing a brand image of the fun American hunk and the prestige of a guarded territory.

This kind of come here-stay back attitude (otherwise known as "the tease") need not only be conveyed through service personnel, but through product delivery and marketing. Thierry Mugler did this with their Angel perfume. It was developed by L'Oréal as a blue perfume, which in itself is not favored by the classic perfume producing community. The thought was that most consumers in their right minds would shy away from spraying anything blue on themselves or their pricey clothes. Furthermore, the bottle design was very heavy and with sharp edges, evoking a sense of danger. All marketing tests said that it would fail, and yet it became a highly successful and coveted item by balancing a close relationship with the customer in boutiques (you really want to grab it- it's so unique and interesting and the fashion pack loves it... and it's price-accessible for the brand) and a strong sense of distance in the marketing (it looks intimidating and difficult).

The Indicator: Luxury demands the type of service that sets the brand on a higher level by providing exceptionally skilled support with the product and presenting an elite attitude without being offensive or overtly intimidating to the target market. A luxury brand is confident in their position (the lifestyle and heritage they represent), does not wish to be all things to everyone, but also acts in a manner that says, "We live in this world, with this group. If you want to be in this particular tribe, we can help."

The Contender: This is not a license to be haughty or snobby towards potential clients. The key is to know your brand image, your brand values, your core client, and the persona you represent, and then... represent that and only that. A luxury brand should have a specific style, attitude, pattern, recipe, heritage, or other defining characteristic which can be conveyed to your clients through your service, product delivery, store atmosphere, website, Twitter stream, etc. Luxury brands go the extra mile in service, both through serving the customer's needs and in conveying the brand image. They should be unbending in excellence.

Status

The visible economy of a brand lies in the way it proves prestige through its ostentation, and the status attached to it. Status is demonstrated through group-affiliation, the degree of ostentation vs. understatement presented by the brand, the display -and recognition- of unique brand values and the buzz surrounding the brand.

A traditional approach to communicating status is made by demonstrating people interacting with the luxury product on a very intimate level, to illustrate how deeply the brand is a part of their lives and personal identities. Hundreds of examples of D&G, Tommy Hilfiger or Burberry ads featuring groups of fresh young things hanging out while wearing the brand come to mind.

A more recent practice is celebrity dressing, which began on a grand scale with Armani in American Gigalo and then swept the Oscars. (Check out Richard Gere getting dressed in Armani for American Gigolo on YouTube.)

Even more recently, product placement has exploded onto the scene, and it's not just your average can of Coke or bag of Pringles on display: today it's couture... enter The Devil Wears Prada, the Sex and the City series, and then the SATC blockbuster movie, and then that second SATC movie that nobody saw.

Video: Sex & The City's Wedding Dress Photoshoot Scene

So, a luxury brand needs some sort of group affiliation to demonstrate status. It's like a marriage: you must choose your group and they must in turn choose you. There are two main points to demonstrating status (and they are not so different from the service points, above): be authentic to the target group, and focus on quality. Every bit of branded communication should say, "This is who I am, and I am the best."

A status symbol that is low-quality is not a symbol of luxury. Attention, brands: you can have a classic or show-off affiliation, be futuristic or retro in design, but if you don't have a defensible level of quality, you haven't got a luxury brand. Furthermore, if the group you claim to be affiliated with doesn't buy into your brand, you're doing something wrong.

*Another point to note: a brand may be chosen to represent a group that is not considered desirable or in line with the brand's image. This typically becomes the catalyst for a rebranding initiative, as was the case with Burberry and the Chavs, but commentary on a perceived misalignment can also result in negative PR, as was the case with Cristal champagne vs. Jay Z and the hip hop community. On the other hand, a brand might opt to realign their image to embrace the new group, as was the case with Courvoisier cognac which saw a sales increase of 30% after the release of Busta Rhymes and P. Diddy's "Pass the Courvoisier" jam in 2002. The group really showed the love in the release of the "Pass the Courvoisier" music video- check it out here. Spokesmen for the cognac industry have credited the hip-hop artists with saving the French liquor (see Palm Beach Post article).

The Indicator: Luxury brand status is demonstrated not solely through the product, but through the brand website, store design, sales staff and marketing. If it's punk status, it should be be the highest quality form of punk and scream it from the mountain top (what's up, Westwood?!). If the brand is based on an Old Hollywood allure, it should work it like Oscar de la Renta. Or combine the two a la Gwen Stefani's L.A.M.B., a relatively new contender.

As an aside on this point, I've been to so many boutiques that have absolutely no personality... or even worse, they have a personality that totally clashes with the brand image they want to convey. A particular store example that comes to mind featured a Japanese zen-like interior which was lovely in its simplicity but did little to convey the upscale American collegiate/streetwear spirit of the brand it was representing. The concept of status was confusing at best, and more realistically was lost altogether within the retail environment which should be an iconic brand temple.

The Contender: Go big or go home! Know who you are. Communicate it across all channels, and seek to build tribes or align with groups that represent the brand image. Be consistent with your identity, and strive to be the best.

Sacrifice

The "true" luxury brands have a nasty habit of seeming to throw money out the window. They depict the destruction or waste of their valuable products to demonstrate the concept that the brand is above a price point: "If you love this, then money is no object to you." You have no worries. Go ahead- spray that champagne everywhere! You can afford another bottle if you get thirsty!

More commonly you'll see a model or celebrity shedding all of their expensive finery and literally getting naked with the product. This demonstrates that the objects being destroyed or discarded are of lesser value to the branded product being marketed. There is no better example of this (that I can think of) than Dior's ad for J'adore with Charleze Theron.

Sacrifice is also commonly demonstrated in branded events where the bar is open, the food is expensive and money appears to be of no concern. This is typical in store openings, collection or product launches and other major sales events, but also in celebratory events marking brand anniversaries and other milestones. My personal favorite was the GQ 50th Anniversary party in Milan a couple of years ago. Hot Chip was playing live, the dance floor was packed, the bar was open, tiny pieces of unidentifiable food were being delivered by tuxedo-ed waiters and James Franco was being herded around the fashion pack by his publicists.

The Indicator: Sacrifice in luxury involves a demonstration that monetary concerns are secondary at best. It's not the money that matters, but the enjoyment derived from the experience. It should be noted, however, that in today's post-recession economy where there is an increased awareness and valuation of ethical consumption, that sacrificial marketing schemes are less favorable among established luxury markets. The showoff trend is still prevalent in emerging luxury markets, while established markets are building favor in more philanthropic endeavors. Then again, who doesn't enjoy a good party?

The Contender: For the newly minted luxury brands, the concept of sacrifice is not often feasible on a grand scale. However, the image can still be achieved through co-branded events, moderate giveaways and events that offer a unique, though not necessarily bank-breaking experience. More typically, the essence of sacrifice can be made efficiently through ads demonstrating a sense of destruction or paring down to the core product, discarding everything else in favor of pure bliss. This tactic is not only a favorite among luxury brands, but is also often the first tactic for mass market brands aiming to re-position in the prestige market. Don't believe me? Check out Nivea's upcoming Spring 2011 campaign featuring a naked Rihanna. The luxury item? Healthy skin.

Prada Retail Technology

It's a few years old, but still cutting edge by most standards. There is so much that can be done for the fashion industry (and retail in general) with today's technology- it's so exciting!

Read MorePart 3: What Is Luxury? Embracing the Immaterial (or, There's No Such Thing as Luxury)

To compete within the luxury market, a product must have a balance between material, immaterial and distance characteristics. However, all points are subjective. In the end, there is no universal luxury product.

The Immaterial: Notoriety or Status

It is obvious that the term ‘luxury‘ implies a high level of quality, which we also understand is subjective. However, most of the value that sets one brand apart from another, in terms of luxury, is immaterial. That is, to say the symbolic properties that are related to identity, whether through self-identity or through status and group-membership. Fashion itself is centered around this concept: beyond clothing ourselves for protection, what we wear is on some level an indication of who we are or who we aspire to be.

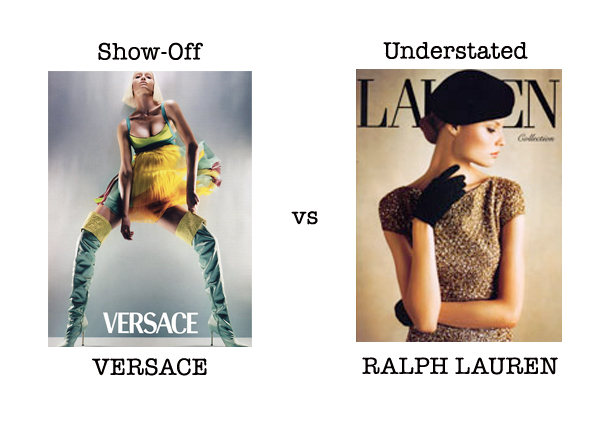

Immaterial values are dependent on the cultural perceptions of luxury in each market. For example, the display of ostentation fluctuates between show-off and understatement, and what is considered to be modest in Miami is different from what is viewed as modest in, say, Vienna. An icon of the show-off class is Paris Hilton, especially in her pre-jail days. Note her shift to represent herself in a more understated way once she faced sentencing: she wanted to demonstrate to the world (and, more likely, the judge) that she had suddenly become more respectable, responsible, and less wild... and that she was willing to "tone it down". However, when you're opening a nightclub called “Vanity“ (and Paris is doing just that), it is pretty clear that ostentation and a show-off attitude are part of your identity (or brand, as it were). Contrast that with the late yet infamous Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, who is still known for her classic, understated elegance. She will likely remain a timeless icon of good taste and class, as her parred down and chic look seem less dated, more refined. Consider the difference in the communication of identity between these two:

The same point can be made for brand identity. Whether in furniture or fashion, architecture or art, each brand or designer has a core identity that fits somewhere between the show-off and understated categories. For example, Versace has built a brand image based on the va-va-voom Botticelli Babe, South Beach, the supermodel society, and bleach, bleach, bleach. Contrast that with Armani's roots in minimalism, androgyny, clean lines and a subtly striking silhouette, or with Ralph Lauren's foundation in American Classic and aristocratic elegance.

Of course, even within one brand there are varying degrees of ostentation, and this is typically presented by way of line diffusion. In order to appeal to different market segments within the broader "luxury market," a brand will often produce a top-level line (haute couture or designer, for example) and then one or more diffusion lines that target a lower price point.

As you move further down a brand's diffusion into these lower price points, logos become increasingly important as quality and innovative design diminish. Armani can produce a basic white t-shirt that looks just like a Hanes, but if they stamp a massive logo across it, a consumer can still feel that they are buying into a piece of the Giorgio Armani lifestyle. That's the idea, anyway.

However, not all brands take this approach. A particular characteristic of French luxury brands is that they are often built around an elegant and iconic figure such as Coco Chanel or Dior's New Look lady, rather than a lifestyle, and these brands often avoid diffusion lines. For this reason, a brand like Chanel is able to offer both understated and show-off looks within the same line, though typically in separate stores, with less variation away from the core look, and always on the same pricing level.

Distance

The factor of distance often stands out as the definitive characteristic of the luxury product in the minds of many consumers. Rarity illuminates the notion of desire; it validates the idea that something is unique, special and somehow worthy of the term luxury. This is why companies like DeBeers take great measures to limit the number of diamonds on the market. More generally, this is also why limited editions are created: limited supply (plus great design, excellent quality and/or spectacular marketing) can create a frenzied sort of demand and support a premium price.

When considering the point of rarity or distance, you'll find that luxury brands go to extreme measures to exaggerate this point (as they well should). Aside from the obvious limited editions, distance is displayed (or hinted at) on every level.

In store merchandising, distance is conveyed by hanging only one or two units/sizes (SKUs) per product, instead of crowding the racks with every item in inventory. You must ask a sales representative for help, and he or she serves as a symbolic barrier between you and the product (any subtle intimidation there serves as an added psychological filter... you're welcome!).

In store displays, rarity comes across in carefully thought-out strategies. The Prada SoHo store displays merchandise like a museum with products arranged in still life settings or behind glass cases. Those Pierre Hermé cake shops in Paris are not designed like jewelry stores just to symbolize the quality of the products; it also communicates a sense of "Hands-off! Rare and precious items here! You can look, but you can't touch."

The Balancing Equation

A company could be said to be competing in the luxury market when they have a balance of three components: the material, the immaterial, and distance.

When one or two of these components are low, the other(s) must be high to compensate. For example, in lower level diffusion lines, where the quality (a material value) is similar to mass market products, the logo (or the immaterial) must be more prominent. If the material value of a Gucci key-chain is quite low, the immaterial value must compensate.

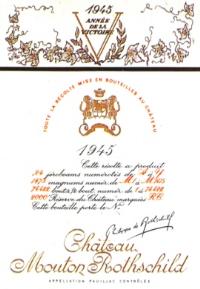

For a very rare and/or high-quality product, the immaterial value need not be so high. In 2006, a bidder at Christie's auction house broke the world record for the highest amount ever paid for a case of wine ($345,000 for a 6-bottle case of magnums). Unlike Gucci or Armani, Ferrari or Porsche, the brand of the wine was unknown to most non-connoisseurs. The wine was Château Mouton-Rothschild 1945. The background story is beautiful (man returns to his family vineyard in Bordeaux after WW2 and the Allied liberation to find his entire world destroyed, rebuilds and produces one of the most glorified wines of all time), the label is special and unique (marked with a V for victory after WW2, commissioned by a French artist and signed by the producer), and the quality of the wine is regarded by connoisseurs worldwide as remarkable.

Material: Is it a high quality wine? Many wine connoisseurs would argue that this Mouton is among the finest wines ever produced, however some would consider it merely good. Is it expensive? I certainly think so, but others might disagree.

Distance: Is it rare? Certainly: there were only so many bottles produced in 1945, so this is definitely a limited edition.

Immaterial: Does it convey status or identity? In some circles, yes; it is very famous. However, unlike many luxury brands that boast near universal fame, this Mouton is known only within more closed, expert circles. But, hey, if that's the group you want to be associated with, Château Mouton-Rothschild 1945 is certainly a hot entry ticket.

In the case of Château Mouton-Rothschild 1945, the material and immaterial properties are relatively subjective, however the rarity of the product is indisputable. Is it luxury? At $28,750 per bottle, and with a story like that, I would certainly consider it a luxury to experience this wine... however, I have been wine tasting in Bordeaux and would consider just about all of it to be luxury. To each their own.

(By the way, there is a great history of the Château Mouton-Rothschild estate and wines here.)

In the end, there really is no definitive luxury product, just a balance between these three points.