French fashion has long been reflective of social and economic hierarchy, illuminating the distinction among classes. Beginning with the Royal Court of the Sun King, France became the capitol of rich fashion. After Charles Worth created the business of haute couture in the 1800s, Paris became the creative center for a business model that has evolved greatly, yet still remains centered around the spirit of haute couture.

French fashion has long been reflective of social and economic hierarchy, illuminating the distinction among classes. Beginning with the Royal Court of the Sun King, France became the capitol of rich fashion. After Charles Worth created the business of haute couture in the 1800s, Paris became the creative center for a business model that has evolved greatly, yet still remains centered around the spirit of haute couture.

What is Couture?

Haute couture is identified as unique pieces constructed with precious materials, made-to-measure, and made for special occasions- not daily wear. A dress of this nature today should run you on average between 20,000 and 30,000 euro and up.

According to French law as of 2008, the following points must be met for a fashion company to be considered a house of couture:

- the atelier must produce at least 50 garments per season by hand

- the atelier must employ at least 20 skilled in-house workers for production

Note: This model is changing under the current economic situation, in order to protect the existing haute couture legacy; too many couturiers were closing their doors under the weight of these expensive restrictions.

Where there were once more than 30,000 clients per year for the highest form of French fashion, today there remain less than 3,000, and most of these are irregular clients. Hence, haute couture is not a big business anymore; it is unaffordable and impractical, as there are fewer and fewer occasions in today's world to wear such items. It has become much less profitable than it once was, having lost the link with modern life.

Most companies that made their name in haute couture today sell primarily accessible products and democratic accessories like lipstick, perfumes, and so on. However, to continue to sell these more "basic" goods at high profit margins, they must continue to produce high fashion. People are now buying the legacy of couture, rather than the couture itself. Therefore, to make the big bucks selling goods at the bottom, you must be positioned at the top.French companies based around haute couture lack a bottom-up business model, and have no second-lines: consider French powerhouses Dior and Chanel, as opposed to Armani, Ralph Lauren, Dolce & Gabbana, etc.

Most companies that made their name in haute couture today sell primarily accessible products and democratic accessories like lipstick, perfumes, and so on. However, to continue to sell these more "basic" goods at high profit margins, they must continue to produce high fashion. People are now buying the legacy of couture, rather than the couture itself. Therefore, to make the big bucks selling goods at the bottom, you must be positioned at the top.French companies based around haute couture lack a bottom-up business model, and have no second-lines: consider French powerhouses Dior and Chanel, as opposed to Armani, Ralph Lauren, Dolce & Gabbana, etc.

The Dream created by the haute couture collection is used to sell cheaper products from the same brand.

Brand images and communications demonstrate a high level of arrogance and provocation, in order to build The Dream. Have you ever wondered how or why that "crazy stuff that nobody is ever going to buy" makes it onto the catwalk? The most elaborate and provocative designs are taken onto the runway because the goal is not to sell as many units as possible, but to demonstrate creativity and uniqueness, and generate buzz around the brand. Consider the wild boys Jean Paul Gaultier for Hermes, or John Galliano for Dior (below).

Brand images and communications demonstrate a high level of arrogance and provocation, in order to build The Dream. Have you ever wondered how or why that "crazy stuff that nobody is ever going to buy" makes it onto the catwalk? The most elaborate and provocative designs are taken onto the runway because the goal is not to sell as many units as possible, but to demonstrate creativity and uniqueness, and generate buzz around the brand. Consider the wild boys Jean Paul Gaultier for Hermes, or John Galliano for Dior (below).

The buzz-factor has become increasingly important for luxury fashion labels in recent years, especially in France where the namesake designers (Dior, Chanel, Vionnet, Yves Saint Laurent, etc) are no longer with us. In fact, most clients are unaware of the designers behind today's major labels. Instead, it is much more common to know which celebrities are wearing which labels (the Poiret legacy lives on!).

The French Fashion System

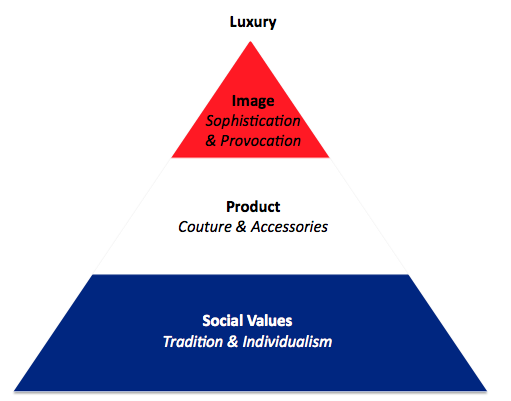

To summarize, the French business model is derived from a long tradition of craft and individualism... and marketing. Couture was the original product of the French fashion and luxury system, which was recently integrated with and then overtaken by accessories. The image of sophistication and provocation are used to produce the sense of luxury at the highest levels of the brand (through couture), which is what the companies are selling (through cosmetics and accessories). Viola!

- Couture = Image

- Accessories/Cosmetics = Sales

Here's my hastily-made visual (with apologies to France):

The crinoline was composed of layers of caging, which attached to the corset to create an S-shape. Women in this costume needed a maid to assist in using the restroom. Movement was very limited, and therefore the only women who could afford to dress in this manner were women of great financial means. Further, the half-crinoline was made from 30m of fabric. It was extremely expensive and VERY HEAVY... for the least active of women. Full underwirings were required for all activities except fencing and swimming. FYI, it was absolutely disgraceful for a woman to be seen in her nightgown, even by her husband.

The crinoline was composed of layers of caging, which attached to the corset to create an S-shape. Women in this costume needed a maid to assist in using the restroom. Movement was very limited, and therefore the only women who could afford to dress in this manner were women of great financial means. Further, the half-crinoline was made from 30m of fabric. It was extremely expensive and VERY HEAVY... for the least active of women. Full underwirings were required for all activities except fencing and swimming. FYI, it was absolutely disgraceful for a woman to be seen in her nightgown, even by her husband. Worth started making dresses that showed off the high quality of the fabrics he had learned about from working as a draper. However, people had become interested in the fashion of the dress instead of just the fabric. They wanted something exciting and exotic. Worth founded his own couture house with much fanfare in Paris in 1858 and was the first designer to gain star status simply by signing each of his creations as if they were works of art. Targeting the European aristocracy and the American market (the world's richest markets, at that time), Worth personally determined what he would make for each client (as opposed to being ordered to make something), and labeled his creations with his own name instead of his clients'. He did not create a new style, but rather elaborated the existing style (reducing the crinoline and introducing trains as luxurious accouterments, and developed interchangeable patters with the use of a sewing machine. He flamboyantly presented a new collection each year using the first live models (his wife and friends), and this introduced the constant factor of change within the fashion industry. Worth lived a very public life as an acting artist, creating a sense of notoriety and developing himself as a brand. Haute couture was thus born.

Worth started making dresses that showed off the high quality of the fabrics he had learned about from working as a draper. However, people had become interested in the fashion of the dress instead of just the fabric. They wanted something exciting and exotic. Worth founded his own couture house with much fanfare in Paris in 1858 and was the first designer to gain star status simply by signing each of his creations as if they were works of art. Targeting the European aristocracy and the American market (the world's richest markets, at that time), Worth personally determined what he would make for each client (as opposed to being ordered to make something), and labeled his creations with his own name instead of his clients'. He did not create a new style, but rather elaborated the existing style (reducing the crinoline and introducing trains as luxurious accouterments, and developed interchangeable patters with the use of a sewing machine. He flamboyantly presented a new collection each year using the first live models (his wife and friends), and this introduced the constant factor of change within the fashion industry. Worth lived a very public life as an acting artist, creating a sense of notoriety and developing himself as a brand. Haute couture was thus born. However, aside from revolutionizing fashion marketing, Worth did little to revolutionize the heavily girdled, contoured and covered “ladylike” look of the femme omee of the Belle Epoch. The French system of haute couture made its debut in Paris with the Pavillon de l”Elegance at the World Fair of 1900. Here, a few select fashion houses including Worth and Doucet showed their spectacular creations to an amazed international audience.

However, aside from revolutionizing fashion marketing, Worth did little to revolutionize the heavily girdled, contoured and covered “ladylike” look of the femme omee of the Belle Epoch. The French system of haute couture made its debut in Paris with the Pavillon de l”Elegance at the World Fair of 1900. Here, a few select fashion houses including Worth and Doucet showed their spectacular creations to an amazed international audience.